| |

|

| |

click an image for more information |

Introduction

Prisons and Prisoners in Walker County Texas |

|

|

Since the creation of the Texas State Penitentiary in 1849 — known locally as the “Walls Unit” — the issues of crime, punishment, and rehabilitation have been central to the lives of Walker County residents. With six separate prisons, including the state’s execution chamber, housing over 8000 prisoners, Huntsville, the seat of Walker Country, has been commonly referred to as Texas’s “prison city.” [1] Yet in addition to housing thousands of inmates convicted of crimes in Texas courts, from 1942 to 1945 Huntsville also housed another sort of prisoner—German and Japanese prisoners of war—captured by Allied soldiers during the Second World War. For over three years army officials and local residents of Walker County struggled to house, feed, guard, and coexist with over 2,000 enemy soldiers. Common problems ran the gamut from scouting out a suitable location for the facility that would come to be known as “Camp Huntsville,” struggling to build rudimentary prison facilities under tight deadlines, regulating the behavior of thousands of prisoners for whom English was not a native language, fighting attempts by diehard Nazi inmates to intimidate other prisoners, all the while attempting to maintain local public support for the camp. In addition, in 1943 the War Department and the Provost Marshall General’s Office selected Camp Huntsville to house a top secret governmental program to enlist local college professors and teachers to educate select German and later Japanese POWs in American history, political traditions, and culture. The story of Camp Huntsville and its fellow Texas POW camps thus sheds important historical light on the attempts made by Army officials, prisoners of war, and ordinary Texans to live together on a day to day basis during perilous times. Since the creation of the Texas State Penitentiary in 1849 — known locally as the “Walls Unit” — the issues of crime, punishment, and rehabilitation have been central to the lives of Walker County residents. With six separate prisons, including the state’s execution chamber, housing over 8000 prisoners, Huntsville, the seat of Walker Country, has been commonly referred to as Texas’s “prison city.” [1] Yet in addition to housing thousands of inmates convicted of crimes in Texas courts, from 1942 to 1945 Huntsville also housed another sort of prisoner—German and Japanese prisoners of war—captured by Allied soldiers during the Second World War. For over three years army officials and local residents of Walker County struggled to house, feed, guard, and coexist with over 2,000 enemy soldiers. Common problems ran the gamut from scouting out a suitable location for the facility that would come to be known as “Camp Huntsville,” struggling to build rudimentary prison facilities under tight deadlines, regulating the behavior of thousands of prisoners for whom English was not a native language, fighting attempts by diehard Nazi inmates to intimidate other prisoners, all the while attempting to maintain local public support for the camp. In addition, in 1943 the War Department and the Provost Marshall General’s Office selected Camp Huntsville to house a top secret governmental program to enlist local college professors and teachers to educate select German and later Japanese POWs in American history, political traditions, and culture. The story of Camp Huntsville and its fellow Texas POW camps thus sheds important historical light on the attempts made by Army officials, prisoners of war, and ordinary Texans to live together on a day to day basis during perilous times.

|

Creating Camp Huntsville

World War II, Prisoners of War, and the Army Corps of Engineers |

|

|

In early November, 1941 the fall of France to the Nazis and the Japanese conquest of large sections of Asia cast a disturbing but dim shadow over the lives of many residents of Walker County, Texas. According to the 1940 census, 19,686 people including 11,047 whites, 8,820 African Americans, and a small community of 162 foreign nationals, most of whom were Hispanic, called Walker County home. [2] To be certain, many Texans sympathized with Allied forces in their struggle against the Axis powers. Yet Texas political leaders such as U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chair Thomas Connelly supported President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s military buildups and lend lease policies primarily for the economic benefits such programs would bring to the Lone Star state. Many local whites likewise remained more concerned with the decline of cotton farming, the rise of cattle ranching, and bank foreclosures in the wake of the Great Depression than world affairs. Local blacks likewise faced their own problems such as the denial of voting and other basic political rights, unequal educational opportunities, and an increase in tenant farming. Many responded to this grim situation by “voting with their feet” and departing in large numbers to northern industrial cities such as Chicago and Detroit. [3] In early November, 1941 the fall of France to the Nazis and the Japanese conquest of large sections of Asia cast a disturbing but dim shadow over the lives of many residents of Walker County, Texas. According to the 1940 census, 19,686 people including 11,047 whites, 8,820 African Americans, and a small community of 162 foreign nationals, most of whom were Hispanic, called Walker County home. [2] To be certain, many Texans sympathized with Allied forces in their struggle against the Axis powers. Yet Texas political leaders such as U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chair Thomas Connelly supported President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s military buildups and lend lease policies primarily for the economic benefits such programs would bring to the Lone Star state. Many local whites likewise remained more concerned with the decline of cotton farming, the rise of cattle ranching, and bank foreclosures in the wake of the Great Depression than world affairs. Local blacks likewise faced their own problems such as the denial of voting and other basic political rights, unequal educational opportunities, and an increase in tenant farming. Many responded to this grim situation by “voting with their feet” and departing in large numbers to northern industrial cities such as Chicago and Detroit. [3]

All of this changed on December 7, 1941 following Japan’s attack on U.S, military forces at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. In the days following the attack U.S. Senator James Connolly of Texas introduced resolutions to declare war on Japan and its allies, Germany and Italy. Texans rushed to volunteer for military service and ultimately provide over 750,000 soldiers for the war effort. [4]

The United States’ entry into the war raised the very real problem of dealing with prisoners of war. The federal government had utilized internment camps in the Civil War, the Plains Wars, the Spanish-American War, and the Philippines Insurrection. But U.S. officials were ill prepared to house potentially hundreds of thousands of foreign born prisoners of war, most of whom spoke not a word of English, on American soil. They therefore turned to the Third Geneva Convention accords, created in 1929 to set international standards for the treatment of prisoners of war, as a baseline for creating a system of POW camps to be located throughout the United States. By 1939 forty nations had signed the Geneva Accords including the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan. The federal government accordingly adopted the Geneva Accords in no small part due to concerns about possible reprisals by Axis officials against American prisoners of war in Europe and Asia. [5] The United States’ entry into the war raised the very real problem of dealing with prisoners of war. The federal government had utilized internment camps in the Civil War, the Plains Wars, the Spanish-American War, and the Philippines Insurrection. But U.S. officials were ill prepared to house potentially hundreds of thousands of foreign born prisoners of war, most of whom spoke not a word of English, on American soil. They therefore turned to the Third Geneva Convention accords, created in 1929 to set international standards for the treatment of prisoners of war, as a baseline for creating a system of POW camps to be located throughout the United States. By 1939 forty nations had signed the Geneva Accords including the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan. The federal government accordingly adopted the Geneva Accords in no small part due to concerns about possible reprisals by Axis officials against American prisoners of war in Europe and Asia. [5]

From the beginning, attempts to create a comprehensive prisoner of war policy were fraught with mishaps. To begin, several different government agencies with overlapping jurisdictions claimed authority for administering POW camps in America. The War Department assumed responsibility for creating the camps, although it authorized the Army Service Forces to run most of the day-to-day affairs of camp life. The State Department, Office of Special War Problems Division, and Provost Marshall General’s Office (PMGO) also clamored to control U.S. prisoner of war policy. This bureaucratic tangle was not resolved until the end of the war in June 1945 when the PMGO received final authority over all POWs still on American soil. [6]

Despite such intergovernmental rivalries, in January 1942 the PMGO issued a report which called for the creation of two internment camps which could hold 3,000 prisoners each—to be located in Roswell, New Mexico and Huntsville, Texas. Roswell and Huntsville were chosen due to political lobbying from local politicians, the availability of cheap land on which to build prisons, and the remoteness of both locations which would discourage escape attempts. Also, as the Geneva Convention required prisoners of war to be detained in climates similar to those in which they had been captured. New Mexico and Texas were therefore logical equivalent for the North African deserts in which many German soldiers had been captured. For these reasons the federal government would also design additional base camps in McLean, Mexia, Hearne, Hereford, and Brady, Texas plus fifty-one smaller “branch camps” across the Lone Star State. These branch camps were primarily designed to provide local farmers with cheap prisoner labor. In fact, by the end of the Second World War Texas would boast twice as many prisoner of war camps than any other individual state. [7]

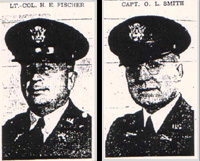

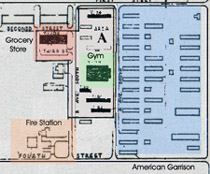

The Army Corps of Engineers quickly surveyed suitable sites around Walker County before finally deciding on a 150 acre parcel of land located eight miles east of Huntsville. The area boasted abundant woods, access to water, gas, electricity, highways, and rail lines, proximity to local farms that would benefit from convict labor, and avoided densely populated areas and other military instillations. The federal government purchased land from local farmers and the Corps of Engineers began construction of “Camp Huntsville” in August 1942. Over the following month a mess hall, infirmary, commissary, laundry, bakery, post office, officer’s club, and gymnasium took shape. Workers also cobbled together sixteen compounds for prisoners with additional barracks for guards and administrative personnel. Over 400 buildings were eventually constructed at Camp Huntsville. Most were built with prefabricated walls, tar paper, corrugated tin roofs, and heated in the winter by potbellied stoves. Barbed wire and electrically charged fences and guard towers with heavy searchlights kept the compounds separate from one another. In September Colonel Fischer, the camp commander, hosted an open house for local residents of Walker County and select members of the media. Yet the actual nature of Camp Huntsville remained a closely guarded military secret until the end of the war. [8] The Army Corps of Engineers quickly surveyed suitable sites around Walker County before finally deciding on a 150 acre parcel of land located eight miles east of Huntsville. The area boasted abundant woods, access to water, gas, electricity, highways, and rail lines, proximity to local farms that would benefit from convict labor, and avoided densely populated areas and other military instillations. The federal government purchased land from local farmers and the Corps of Engineers began construction of “Camp Huntsville” in August 1942. Over the following month a mess hall, infirmary, commissary, laundry, bakery, post office, officer’s club, and gymnasium took shape. Workers also cobbled together sixteen compounds for prisoners with additional barracks for guards and administrative personnel. Over 400 buildings were eventually constructed at Camp Huntsville. Most were built with prefabricated walls, tar paper, corrugated tin roofs, and heated in the winter by potbellied stoves. Barbed wire and electrically charged fences and guard towers with heavy searchlights kept the compounds separate from one another. In September Colonel Fischer, the camp commander, hosted an open house for local residents of Walker County and select members of the media. Yet the actual nature of Camp Huntsville remained a closely guarded military secret until the end of the war. [8] |

LIfe in a Prisoner of War Camp

German POWs in the Huntsvillle Camp |

|

|

The completion of Camp Huntsville could not have come at a better time for Army officials. In November 1942, 150,000 German and Italian soldiers, many of whom were veterans of General Irwin Rommel’s Afrika Corps, surrendered to Allied forces following the Second Battle of El Alamein in North Africa. The prisoners were herded aboard ships bound for Boston, Massachusetts, New York City, or Norfolk, Virginia. Upon arriving in the United States, the soldiers were processed and shipped aboard trains to prisoner of war camps throughout the nation. [9] The completion of Camp Huntsville could not have come at a better time for Army officials. In November 1942, 150,000 German and Italian soldiers, many of whom were veterans of General Irwin Rommel’s Afrika Corps, surrendered to Allied forces following the Second Battle of El Alamein in North Africa. The prisoners were herded aboard ships bound for Boston, Massachusetts, New York City, or Norfolk, Virginia. Upon arriving in the United States, the soldiers were processed and shipped aboard trains to prisoner of war camps throughout the nation. [9]

In spring 1943 the first group of German prisoners arrived at Camp Huntsville. Walker County residents gathered in Huntsville to watch the prisoners of war arrive by train. One local woman noted the disheveled look of the prisoners and commented that the train cars in which they had been housed smelled, “worse than a cattle car.” Nevertheless, the soldiers marched three miles through the Texas heat to Camp Huntsville in perfect formation singing German military songs.10

Upon arriving at Camp Huntsville, prisoners were fingerprinted and photographed and then divided into 250 men companies and housed in separate compounds under the command of POW German officers. Camp life began with reveille every morning at 5:45 a.m. Prisoners showered and shaved, ate breakfast, and then reported to work details, with break for lunch. In the evenings after supper prisoners had limited free time to pursue crafts, hobbies, attend classes, or exercise. The day ended with taps at 10:00 p.m. Upon arriving at Camp Huntsville, prisoners were fingerprinted and photographed and then divided into 250 men companies and housed in separate compounds under the command of POW German officers. Camp life began with reveille every morning at 5:45 a.m. Prisoners showered and shaved, ate breakfast, and then reported to work details, with break for lunch. In the evenings after supper prisoners had limited free time to pursue crafts, hobbies, attend classes, or exercise. The day ended with taps at 10:00 p.m.

Colonel Fischer and his officers operated under the assumption that prisoners with relatively good morale and sufficient distractions would not cause problems for their captors. Tentative privileges given to prisoners could also be taken away in the case of bad behavior. For instance, prisoners were allowed to keep their uniforms, medals, and rank insignias, provided that they were stamped with the letter “P” to signify their status. Inmates were also allowed to elect from among their ranks a camp spokesman, to act as a liaison between the prisoners and the camp staff. [11]

To keep prisoners occupied, army officials at Camp Huntsville provided them with games, sports equipment, books, radios, and phonographs. Prisoners were also encouraged to form bands, orchestras, choir groups, and attend Protestant and Catholic religious services delivered in German and English presided over by Army chaplains and local ministers. Model prisoners were also allowed to attend classes on English, American history, German literature, and math taught by fellow POWs who served as instructors. The Red Cross and other also charitable organizations contributed books to construct a camp library. By 1944 the Camp Huntsville library boasted over 2,000 books, magazines, and newspapers, many of which were in German. [12]

In August 1943 the Pentagon and the War Manpower Commission in Washington DC drafted a program which allowed prisoner of war camps to provide POW labor to local farms and businesses to help compensate for manpower shortages brought about by the war. Under Article 12 of the Geneva Accords enemy soldiers could be used as a labor force, provided they be paid a minimum of $.10 a day. Colonel C. R. Carvolth, the newly appointed camp commander of Camp Huntsville who had recently replaced Colonel Fischer, quickly seized on the program as both a way to keep prisoners too tired to cause trouble and a method to cultivate good will among local Walker County residents. From 1943 to 1945 prisoners at Camp Huntsville and other local POW camps “picked peaches and citrus fruits, harvested rice, cut wood, baled hay, threshed grain, gathered pecans, and chopped records amounts of cotton.” [13] In August 1943 the Pentagon and the War Manpower Commission in Washington DC drafted a program which allowed prisoner of war camps to provide POW labor to local farms and businesses to help compensate for manpower shortages brought about by the war. Under Article 12 of the Geneva Accords enemy soldiers could be used as a labor force, provided they be paid a minimum of $.10 a day. Colonel C. R. Carvolth, the newly appointed camp commander of Camp Huntsville who had recently replaced Colonel Fischer, quickly seized on the program as both a way to keep prisoners too tired to cause trouble and a method to cultivate good will among local Walker County residents. From 1943 to 1945 prisoners at Camp Huntsville and other local POW camps “picked peaches and citrus fruits, harvested rice, cut wood, baled hay, threshed grain, gathered pecans, and chopped records amounts of cotton.” [13]

Farmers appeared appreciative of the extra labor and often maintained close, personal ties with the German soldiers. Money earned by prisoners could be used to purchase extra clothing, food, alcohol, and other luxuries at the camp canteen. In fact, prisoners at Camp Huntsville accumulated so many credits that camp personnel had difficulty keeping the canteen filled with goods for prisoners to purchase. [14] |

The Nazi Problem

Dangerous POWs at Camp Huntsvillle |

|

|

Despite the encouraging beginning at Camp Huntsville, problems soon developed there and at similar camps across Texas. Army engineers had initially designed Camp Huntsville to house a maximum of 3,000 prisoners. Yet new arrivals, many of them committed Nazi non-commissioned officers rejected by other POW camps, continued to appear through the summer and fall of 1943. By October Camp Huntsville housed 4,840 prisoners and Army personnel were kept busy constructing additional barracks and facilities for the additional prisoners. In addition, food shortages meant that prisoners were periodically kept on strict rations or forced to eat similar, unfamiliar meals day after day. Chronic mail shortages also kept prisoners worried about their families in Germany and the progress of the war. [15] Despite the encouraging beginning at Camp Huntsville, problems soon developed there and at similar camps across Texas. Army engineers had initially designed Camp Huntsville to house a maximum of 3,000 prisoners. Yet new arrivals, many of them committed Nazi non-commissioned officers rejected by other POW camps, continued to appear through the summer and fall of 1943. By October Camp Huntsville housed 4,840 prisoners and Army personnel were kept busy constructing additional barracks and facilities for the additional prisoners. In addition, food shortages meant that prisoners were periodically kept on strict rations or forced to eat similar, unfamiliar meals day after day. Chronic mail shortages also kept prisoners worried about their families in Germany and the progress of the war. [15]

Yet in addition to mundane problems, camp officials were constantly beset by conflicts from within the POW community. Many of the Afrika Corps soldiers at Camp Huntsville were dedicated, combat hardened Nazis (including large numbers of Gestapo agents and SS troops) taken relatively early in the war. Many other prisoners, however, were members of the 999th Probation Division, an unlikely combination of petty criminals and anti-Nazi journalists, intellectuals, artists, and socialists imprisoned by Adolph Hitler. When German manpower became scare they were drafted into the German army and sent to North Africa to fight. After the D-Day invasion of June 6, 1944 many young German conscripts and older German reservists were taken prisoner by Allied forces and sent to Camp Huntsville. [16]

Under Article 4 of the Geneva Accords “differences in treatment among prisoners is lawful only when it is based on the military rank, state of physical or mental health . . .” Army officials therefore made no attempt to segregate prisoners based upon personal beliefs. As a result, Pro-Nazi, neutral, and Anti-Nazi soldiers were thrown into rough proximity at Camp Huntsville and other prisoner of war camps with little effort to segregate them. According to historian Arnold Krammer, the army missed a crucial opportunity to interrogate and separate newly captured prisoners while they were still disoriented and “the best opportunity to segregate the various shades of political ideology had passed, and totalitarian reinforcement was allowed to take place.” [17] Under Article 4 of the Geneva Accords “differences in treatment among prisoners is lawful only when it is based on the military rank, state of physical or mental health . . .” Army officials therefore made no attempt to segregate prisoners based upon personal beliefs. As a result, Pro-Nazi, neutral, and Anti-Nazi soldiers were thrown into rough proximity at Camp Huntsville and other prisoner of war camps with little effort to segregate them. According to historian Arnold Krammer, the army missed a crucial opportunity to interrogate and separate newly captured prisoners while they were still disoriented and “the best opportunity to segregate the various shades of political ideology had passed, and totalitarian reinforcement was allowed to take place.” [17]

From spring 1943 to spring 1945 Pro-Nazi forces consolidated their hold over the POW population of Camp Huntsville. Just as Nazi party leaders had seized power in Germany through intimidation, force, and propaganda, so too Nazi POWs used “Gestapo” methods to enforce obedience from fellow inmates. For instance, Pro-Nazi German officers demanded and received key POW positions such as camp spokesman, librarian, and instructors for the camp’s education program. Gestapo and SS officers censored mail, turned campus classes into Nazi indoctrination sessions, delivered weekly readings from Mein Kampf, and proudly displayed Nazi flags and pictures of Hitler and other German leaders on barracks walls. POWs who refused to toe the Nazi line faced the wrath of informal German “honor courts” which frequently confined soldiers to quarters or fined them. More painful punishments included “holy ghost treatments” by which a sleeping prisoner was tied to his bed and a pillow case thrust over his face in preparation for a savage beating. In several cases Nazi officers demanded that prisoners commit suicide or risk having their names forwarded to officials in Germany who would carry out reprisals against the victim’s families. [18]

German officers at Camp Huntsville also maintained detailed lists of loyal Nazi party members and suspected collaborators. From March 1944 to February 1945 Nazi prisoners infiltrated the post office at nearby Camp Hearne, which distributed mail to all POW camps in the American southwest. The POWs used old envelopes with censors stamps already attached to send uncensored mail to contacts. The post office workers compiled extensive lists of anti-Nazi prisoners and passed them on to their comrades-in-arms at Camp Huntsville. [19]

Nazi domination of POW camps throughout the United States was fueled by several factors. Faced with the difficulties of fighting a two front war, the U.S. Army often staffed prisoner of war camps with officers unfit for field commands or retired reserve officers. As scholar Judith M. Gansberg notes, “[m]en were selected in haphazard fashion, often merely because they knew a few words of German. They were sent in to face the fires of National Socialism, the most fanatic of all contemporary political philosophies, yet they were untrained, unskilled, and unaware of what to do to smother the flames.” [20] Political rivalries between camp commanders and local military base officers, conflicting federal agencies, and a general apathy on the part of camp guards towards their prisoners only exacerbated matters. Prison guards were also in short supply and camp officials often had to rely on German officers to control their men. Since prison officials were bound by the Geneva Accords, prisoners not charged with specific crimes could only be punished by losing their movie, recreation, or canteen privileges. [21] Some camp commanders became so disgusted with the situation that they actually entered informal agreements with Nazi POW leaders. For instance, in Camp Concordia, Kansas local army officials gave Nazi officers wide latitude in controlling their fellow prisoners provided that the camp continued to run efficiently.[22] Nazi domination of POW camps throughout the United States was fueled by several factors. Faced with the difficulties of fighting a two front war, the U.S. Army often staffed prisoner of war camps with officers unfit for field commands or retired reserve officers. As scholar Judith M. Gansberg notes, “[m]en were selected in haphazard fashion, often merely because they knew a few words of German. They were sent in to face the fires of National Socialism, the most fanatic of all contemporary political philosophies, yet they were untrained, unskilled, and unaware of what to do to smother the flames.” [20] Political rivalries between camp commanders and local military base officers, conflicting federal agencies, and a general apathy on the part of camp guards towards their prisoners only exacerbated matters. Prison guards were also in short supply and camp officials often had to rely on German officers to control their men. Since prison officials were bound by the Geneva Accords, prisoners not charged with specific crimes could only be punished by losing their movie, recreation, or canteen privileges. [21] Some camp commanders became so disgusted with the situation that they actually entered informal agreements with Nazi POW leaders. For instance, in Camp Concordia, Kansas local army officials gave Nazi officers wide latitude in controlling their fellow prisoners provided that the camp continued to run efficiently.[22]

Throughout the spring and summer of 1943 conditions at Camp Huntsville continued to deteriorate as Pro-Nazi POWs began to not only terrorize other prisoners but also directly challenge the authority of their captors. In June a camp guard shot POW Anton Fischwaller for attempting to escape. The following day a second guard shot at a prisoner attempting to scale one of the camp walls but missed, hitting an innocent German soldier by mistake. [23] Perhaps in retaliation for this incident, four months later an inmate attacked a camp guard and received a court martial and a six month stay in solitary confinement for his efforts. In a separate incident four prisoners were accused of beating an U.S. Army officer. Although two of the accused were exonerated, the remaining two received eighteen months of hard labor at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. [24]

The most serious threat to camp security came on the night of November 25, 1943 when a group of Pro-Nazi prisoners attacked a group of Anti-Nazi POWs with clubs and effectively blocked guards from breaking up the fight. The entire incident in turn proved to be a distraction for a second group of soldiers who delivered a “holy ghost treatment” to a German Catholic Priest in the camp who was an outspoken critic of the Nazi Party. Camp guards shot and killed one of the rioters and order was quickly restored. Several weeks later Nazi POWs delivered a second Holy Ghost beating to Hans Wilfanger, an Austrian who had been drafted into the German army and who was a known collaborator with British and American authorities. [25] It therefore came as little surprise when Reverend Maurice M. Hall, the Camp Huntsville Chaplain, told the Baptist General Convention in Dallas, Texas that 60% of the POWs at Camp Huntsville were “confirmed Nazis” and suggested that “you might as well preach Christianity to a wall as these Hitlerites.” The fact that a Baptist Minister could be compelled to castigate potential converts as “treacherous, mad, and fanatical with their dogma,” revealed just how serious conditions at Camp Huntsville had become. The most serious threat to camp security came on the night of November 25, 1943 when a group of Pro-Nazi prisoners attacked a group of Anti-Nazi POWs with clubs and effectively blocked guards from breaking up the fight. The entire incident in turn proved to be a distraction for a second group of soldiers who delivered a “holy ghost treatment” to a German Catholic Priest in the camp who was an outspoken critic of the Nazi Party. Camp guards shot and killed one of the rioters and order was quickly restored. Several weeks later Nazi POWs delivered a second Holy Ghost beating to Hans Wilfanger, an Austrian who had been drafted into the German army and who was a known collaborator with British and American authorities. [25] It therefore came as little surprise when Reverend Maurice M. Hall, the Camp Huntsville Chaplain, told the Baptist General Convention in Dallas, Texas that 60% of the POWs at Camp Huntsville were “confirmed Nazis” and suggested that “you might as well preach Christianity to a wall as these Hitlerites.” The fact that a Baptist Minister could be compelled to castigate potential converts as “treacherous, mad, and fanatical with their dogma,” revealed just how serious conditions at Camp Huntsville had become. |

The Intellectual Diversion Program

The Idea Factory and Reeducation for POWs |

|

|

Military officials in Washington DC were slow to realize the severity of problems at Camp Huntsville and other base camps across Texas. Faced with repeated reports of violence in multiple locations, the War Department at first suspected Anti-Nazi POWs as responsible. After all, many Anti-Nazis had been at the center of violent incidents in several camps and many remained reluctant to speak out for fear of reprisals from their fellow prisoners. The army therefore used an intelligence test as an excuse to secretly distinguish the ideological leanings of different prisoners. By the spring of 1943 army officials began to identify the true culprits. [26] Military officials in Washington DC were slow to realize the severity of problems at Camp Huntsville and other base camps across Texas. Faced with repeated reports of violence in multiple locations, the War Department at first suspected Anti-Nazi POWs as responsible. After all, many Anti-Nazis had been at the center of violent incidents in several camps and many remained reluctant to speak out for fear of reprisals from their fellow prisoners. The army therefore used an intelligence test as an excuse to secretly distinguish the ideological leanings of different prisoners. By the spring of 1943 army officials began to identify the true culprits. [26]

In March 1943 U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall received a briefing on the situation and asked Brigadier General Frederick Osborn, Chief of the Morale Branch of the War Department, to counter Nazi influence in American POW camps through a “re-education program” by which “prisoners of war might be exposed to the facts of American history, the workings of a democracy and the contributions made to America by peoples of all national origins.” Osborn forwarded the project to official army historian and Brigadier General S.L.A. Marshall who drafted a blueprint for a reeducation program. The plan was in turn submitted to the U.S. Provost Marshall General Allen Guillon. Perhaps due to rivalries between the War Department and Provost Marshall’s Office, Guillon dismissed the plan as a waste of wartime resources and ordered the project indefinitely shelved. [27]

The reeducation plan might have died in its infancy if not for the efforts of syndicated newspaper columnist and leading Progressive Dorothy Thompson. A larger than life figure, Thompson had interviewed Adolph Hitler in 1931 only to be expelled from Germany three years later. According to rumor she had punched a woman for making Pro-Nazi comments and had delivered a "bronx cheer" at a German Bund Rally in Madison Square Garden. In early 1944 she began to investigate the beating and murders at POW camps in Texas and other states and was horrified at what she saw. She discussed the matter with her friend Eleanor Roosevelt and promoted the idea of a program to teach German prisoners of war the finer points of American history and political traditions. Roosevelt in turn informed her husband of the situation and invited Major Maxwell McKnight, the Administrative Head of Prisoner of War Camp Operations, to the White House for supper. [28]

McKnight was a Yale trained scholar from a prominent New York family on close terms with the Roosevelts. He used such clout to urge Franklin Roosevelt, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, and Secretary of State Edward Stettinius to support such a program. Stimson, in particular, dismissed the plan as counterproductive. Yet with Roosevelt’s continued backing and McKnight’s promise that the program would remain strictly voluntary on the part of the prisoners and in any case kept top secret (not even Congress would learn of the plan until the end of the war), Stimson finally relented. In August the War Department issued a memo voicing support for a program “to give the prisoners of war the facts, objectively presented but so selected and assembled as to correct misinformation and prejudices.” [29] McKnight was a Yale trained scholar from a prominent New York family on close terms with the Roosevelts. He used such clout to urge Franklin Roosevelt, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, and Secretary of State Edward Stettinius to support such a program. Stimson, in particular, dismissed the plan as counterproductive. Yet with Roosevelt’s continued backing and McKnight’s promise that the program would remain strictly voluntary on the part of the prisoners and in any case kept top secret (not even Congress would learn of the plan until the end of the war), Stimson finally relented. In August the War Department issued a memo voicing support for a program “to give the prisoners of war the facts, objectively presented but so selected and assembled as to correct misinformation and prejudices.” [29]

Lieutenant Colonel Edward Davison, a British literature professor, served as Director of the newly formed Special Projects Division, which ran the reeducation program. With McKnight working as his assistant, Davison recruited a variety of academics in March, 1944 to develop a curriculum for educating prisoners of war about American history, politics, and society through the coordinated use of lectures, movies, music, art, and print media. Davison hope that such an agenda would at worst impress Axis POWs with the vitality of American institutions and culture and therefore make them more manageable. At best such POWs might form the nucleus for Pro-American German and Japanese government in the postwar period. The central problem with the reeducation program was that it violated the Geneva Accord’s ban on political indoctrination. Davison thus cleverly packaged the program as a voluntary “intellectual diversion” which would be legal under Article 17 of the Geneva Accords. Accordingly, the reeducation policy came to be known as the “Intellectual Diversion Program.” [30]

Harvard Dean Howard Mumford Jones served as a civilian advisor to the project. Given their classical education backgrounds, Jones, Davison, and McKnight hired likeminded humanities professors and eight-five academically inclined German prisoners of war who believed in rationale discourse. Psychologists and sociologists trained in behavior modification were intentionally excluded from the program. The Intellectual Diversion Program staff met at Fort Kearney, Rhode Island, which they quickly dubbed the “Idea Factory.” These “factory workers” translated American history and literature books into German, selected movies, documentaries, and newsreels to show German POWs, and published a biweekly newspaper called Der Ruf (The Call) to be distributed at POW camps across America. [31] |

Implementing the Intellectual Diversion Program

Reeducation Comes to Camp Huntsvillle |

|

|

Although the intellectuals and scholars at the Idea Factory established the basic parameters of the Intellectual Diversion Program, it fell to the Special Projects Division and the Provost Marshall General’s Office to implement the project. In summer 1944 the PMGO created a special school in New York to provide military officers, many with civilian backgrounds in journalism, education, and literature, with a ten day crash course in the German language, how to motivate prisoners of war, and teaching methods. In keeping with the secretive nature of the Intellectual Diversion program, graduates of the school received the innocuous sounding title of “assistant executive officer” (AEO). By November, 1944 375 AEOs had been assigned to prisoner of war camps throughout the United States. [32] Although the intellectuals and scholars at the Idea Factory established the basic parameters of the Intellectual Diversion Program, it fell to the Special Projects Division and the Provost Marshall General’s Office to implement the project. In summer 1944 the PMGO created a special school in New York to provide military officers, many with civilian backgrounds in journalism, education, and literature, with a ten day crash course in the German language, how to motivate prisoners of war, and teaching methods. In keeping with the secretive nature of the Intellectual Diversion program, graduates of the school received the innocuous sounding title of “assistant executive officer” (AEO). By November, 1944 375 AEOs had been assigned to prisoner of war camps throughout the United States. [32]

One of the first tasks the Assistant Executive Officers had to contend with upon arriving at their duty assignments was to determine which POWs were capable of reeducation. Ironically they turned to an old concept—segregation—for dealing with the problem. As Maxwell McKnight later recalled “We never anticipated segregating despite our experiences in the Deep South . . . We never had a theory of segregating Nazis from anti-Nazis. We could do it on the basis of color, but on the basis of ideology? This never occurred to us.” [33]

Working with camp intelligence officers, the AEOs conducted a series of tests to determine the ideological leanings of individual prisoners. Devout Nazis were referred to as “blacks,” prisoners who had been drafted in the German army were referred to as “grays,” and prisoners that had opposed the Nazis were called “whites.” New camp wide elections were also held for camp spokesman, director of studies, and librarian in which secret ballots were used to help dilute Nazi influence over fellow prisoners. Daily reports of the war were also read over the camp public address system in both German and English to undercut Nazi rumors that the Axis powers were winning the war. [34]

The administrative executive officers also distributed German books previously banned by Hitler, and American works such as Carl Van Doren’s American Literature, Harvey Townsend’s Philosophic Ideas in the United States, Howard Munford Jones’ Ideas in America, Charles Beard’s The Republic, and Samuel Eliot Morison’s Admiral of the Ocean Sea. Voluntary academic classes were also once again permitted, only now taught by Army officers or professors from the nearby Sam Houston State Teacher’s College. Prisoners could even earn college credits through correspondence courses with SHSTC and other area college such as the University of Texas and Baylor University. In addition to distributing copies of Der Ruf, AEOs urged prisoners to write and publish their own camp newspapers. For instance, Camp Huntsville POWs produced a weekly newsletter called Die Fanfare which included articles on local and international news, local football scores, book and movie reviews, and practical articles on how to survive camp life. [35] The administrative executive officers also distributed German books previously banned by Hitler, and American works such as Carl Van Doren’s American Literature, Harvey Townsend’s Philosophic Ideas in the United States, Howard Munford Jones’ Ideas in America, Charles Beard’s The Republic, and Samuel Eliot Morison’s Admiral of the Ocean Sea. Voluntary academic classes were also once again permitted, only now taught by Army officers or professors from the nearby Sam Houston State Teacher’s College. Prisoners could even earn college credits through correspondence courses with SHSTC and other area college such as the University of Texas and Baylor University. In addition to distributing copies of Der Ruf, AEOs urged prisoners to write and publish their own camp newspapers. For instance, Camp Huntsville POWs produced a weekly newsletter called Die Fanfare which included articles on local and international news, local football scores, book and movie reviews, and practical articles on how to survive camp life. [35]

In addition to taking college courses and producing newsletters, prisoners were also encouraged to watch movies preapproved by the Idea Factory which trumpeted the virtues of American civilization. Abe Lincoln of Illinois, The Adventures of Mark Twain, Back to Bataan, Guadalcanal Diary, Land of Liberty, This is America, and Why We Fight were often featured films. After knowledge of the Holocaust became common in 1944 camp officials began to show newsreels which documented the liberation of Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

The Intellectual Diversion Program continued in force until V-E Day on May 8, 1945 and the final repatriation of German prisoners from July 1945 to July 1946. On May 28, 1945, after months of denials, the U.S. government finally admitted the existence of the reeducation program. [36] Given the short lifespan of the program, it was hard to gauge its effectiveness. For instance, many German POWs were openly contemptuous of Der Ruf which they considered to be not only propaganda but too abstractly written to be understood by laymen. Likewise, many prisoners of war simply declined to read books or attend lectures they did not agree with. Prisoners also complained about Holocaust documentaries which they dismissed as Knochhenfilmen or “bone films.” In fact, a survey conducted after the war on 20,000 former POWs found that two-thirds believed the films to be faked by the American government. Yet declines in violence throughout Camp Huntsville and other prisoner of war camps in 1944-1945 suggest that that the Intellectual Diversion Program played a role in weakening Nazi solidarity within the camps, if not necessarily creating legions of prisoners enamored with American culture. [37] |

Reeducating Japanese Prisoners of War

Reeducation Comes to Camp Huntsvillle |

|

|

By the end of the War in Europe in May 1945 the U.S. government could claim only limited success in reeducating German POWs. Yet a month earlier Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy and Dr. Charles W. Hepner of the Office of War Information had already begun to consider ways to take the lessons learned over the past two years in instructing German prisoners of war and put such information to use on Japanese prisoners. Hepner, an expert in Japanese culture with thirty years of experience of living in Asia, carried great weight in governmental circles. McCloy and Hepner sought to convince Secretary of War Stimson that such a program would not only create future Pro-American government officials in Japan but might also serve as a model for the reeducation of the entire Japanese population. [38] By the end of the War in Europe in May 1945 the U.S. government could claim only limited success in reeducating German POWs. Yet a month earlier Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy and Dr. Charles W. Hepner of the Office of War Information had already begun to consider ways to take the lessons learned over the past two years in instructing German prisoners of war and put such information to use on Japanese prisoners. Hepner, an expert in Japanese culture with thirty years of experience of living in Asia, carried great weight in governmental circles. McCloy and Hepner sought to convince Secretary of War Stimson that such a program would not only create future Pro-American government officials in Japan but might also serve as a model for the reeducation of the entire Japanese population. [38]

Over the course of the war, federal officials had been less worried about the morale and conduct of Japanese prisoners of war simply because the number of Japanese POWs paled in significance to German prisoners. On July 18, 1945 Secretary of War Henry Stimson authorized a plan to instruct a select number of Japanese prisoners to be housed at Camps Huntsville, Kenedy, and Hearne, Texas on the benefits of American political and social traditions. Lieutenant Colonel Boude C. Moore, who came from a missionary family, had spent seventeen years in Japan, and spoke fluent Japanese, agreed to spearhead the program. Presumably to give the project an additional veneer of authority, Dr. Hepner agreed to serve as a civilian advisor. [39]

In June 1945 Japanese prisoners of war were tested at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin and separated into “cooperative” and “non-cooperative” groups. Moore and Hepner then handpicked 200 Japanese soldiers who were further divided into three additional groups—soldiers willing to participate in reeducation programs, POWs who were generally cooperative, and prisoners who held the potential to be cooperative. Camp Huntsville was selected as the final site for the program due to its remoteness and prior experience with reeducating prisoners. Colonel Moore and his staff arrived in Huntsville in September 1945 and the prisoners arrived a month later. Given his previous encounters with German prisoners of war, Colonel Carvolth remained skeptical that Japanese prisoners could learn to appreciate American institutions. Yet prompt action on the part of Carvolth and Moore prevented a group of Japanese prisoners from intimidating their fellow inmates in a manner reminiscent of Pro-Nazi prisoners at Camp Huntsville two years earlier. The offending prisoners were transferred, leaving only 186 prisoners to undergo reeducation. [40] In June 1945 Japanese prisoners of war were tested at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin and separated into “cooperative” and “non-cooperative” groups. Moore and Hepner then handpicked 200 Japanese soldiers who were further divided into three additional groups—soldiers willing to participate in reeducation programs, POWs who were generally cooperative, and prisoners who held the potential to be cooperative. Camp Huntsville was selected as the final site for the program due to its remoteness and prior experience with reeducating prisoners. Colonel Moore and his staff arrived in Huntsville in September 1945 and the prisoners arrived a month later. Given his previous encounters with German prisoners of war, Colonel Carvolth remained skeptical that Japanese prisoners could learn to appreciate American institutions. Yet prompt action on the part of Carvolth and Moore prevented a group of Japanese prisoners from intimidating their fellow inmates in a manner reminiscent of Pro-Nazi prisoners at Camp Huntsville two years earlier. The offending prisoners were transferred, leaving only 186 prisoners to undergo reeducation. [40]

From September to December 1945 Moore worked with professors from Sam Houston State Teachers College to create classes on American history, politics, and culture for the Japanese POWs. Some lectures entitled “Fundamental Rights of Man as Set Forth in the Bill of Rights,” “Some of the Essential Points of Democracy,” “The Main Points in the Declaration of Independence,” and The Necessity of a Free Mind in the Search of Truth” discussed the proud history of American democracy. Other lectures such as “Contrasts between Pseudo-Freedom in Japan and Real Freedom in America,” “The Need for Opportunity in Japan for Building a Liberal Democratic Nation,” and “The Objective of Military Government in Japan” likewise stressed the bright egalitarian future which Japan might enjoy if only it would only adopt American style principles of government. Lecture outlines and notes were translated into Japanese, prisoners were given weekly assignments to enhance their knowledge of American history, and daily lessons in English were also allowed. As with the German prisoners of war, the Japanese also watched patriotic American movies and newsreels and worked at Camp Huntsville for limited income. [41]

Throughout the fall of 1945 problems with the Japanese prisoners were kept to a minimum. American authorities now had some experience in reeducating prisoners of war. In any case, the number of Japanese prisoners at Camp Huntsville was small and relatively easy to manage. The Japanese reeducation program might have served as a model for similar projects at other prisoner of war camps throughout the United States. Yet with no advance warning the War Department ordered the program halted on December 15, 1945. The Japanese prisoners at Camp Huntsville were transferred to a holding camp at Lamont, California and repatriated to Japan the following spring. [42] The end of the Second World War in August 1945 may have played a role in the decision to end the Japanese reeducation program. The recently commissioned Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers in Japan, General Douglas MacArthur, may have felt it was more productive to train Japanese soldiers together with Japanese civilians in their home country. No follow up study was ever conducted to determine what, if any, effect U.S. reeducation policies had on the 186 Japanese prisoners who spent time at Camp Huntsville. The Provost Marshall’s Office, however, reported that “although the POWs were rather slow to adapt and respond favorably to the project, the majority came to accept the program and its intent, and that by the time of repatriation the vast majority expressed attitudes indicating that they accepted democratic ideals.” [43] Throughout the fall of 1945 problems with the Japanese prisoners were kept to a minimum. American authorities now had some experience in reeducating prisoners of war. In any case, the number of Japanese prisoners at Camp Huntsville was small and relatively easy to manage. The Japanese reeducation program might have served as a model for similar projects at other prisoner of war camps throughout the United States. Yet with no advance warning the War Department ordered the program halted on December 15, 1945. The Japanese prisoners at Camp Huntsville were transferred to a holding camp at Lamont, California and repatriated to Japan the following spring. [42] The end of the Second World War in August 1945 may have played a role in the decision to end the Japanese reeducation program. The recently commissioned Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers in Japan, General Douglas MacArthur, may have felt it was more productive to train Japanese soldiers together with Japanese civilians in their home country. No follow up study was ever conducted to determine what, if any, effect U.S. reeducation policies had on the 186 Japanese prisoners who spent time at Camp Huntsville. The Provost Marshall’s Office, however, reported that “although the POWs were rather slow to adapt and respond favorably to the project, the majority came to accept the program and its intent, and that by the time of repatriation the vast majority expressed attitudes indicating that they accepted democratic ideals.” [43] |

Public Reaction to Camp Huntsville

Local Residents Respond to the Camp and Its Personnel |

|

|

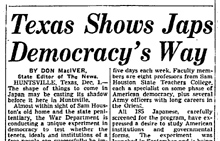

The issue of the effectiveness of Camp Huntsville and other Texas prisoner of war camps in general and the prisoner reeducation programs they utilized lasted long after World War II. During the war Texas, businessmen and farmers who benefitted from the cheap labor provided by POWs tended to support the camps and their reeducation programs. But many other voices—Texans who did not benefit from POW labor, Union leaders, and blue collar Texans who saw the prisoners as competitors for jobs—criticized federal prisoner of war policy in Texas. Such attacks became particularly loud following the invasion of Western Europe as Allied casualties mounted and evidence of the Holocaust came to light. In spring 1945 the offices of Texas Congressmen, the War Department, and the Provost Marshall General were flooded by angry letters from Texans claiming that POW camp commanders were “coddling” prisoners with good food, spacious accommodations, ample opportunities for leisure, and opportunities to earn extra money. Texas newspapers such as the Fort Worth Star Telegram and the San Antonio Express wrote exposés criticizing camp officials for inefficiency and favorable treatment towards their prisoners. After the war, the Provost Marshall’s Office admitted that attempts to keep the Intellectual Diversion Program secret and allowing only limited media access to the camps had ironically sparked public interest in the matter and led to a negative public reaction against such programs. However, the war ended before any sustained criticism could prompt the federal government to change its prisoner of war policies. [44] The issue of the effectiveness of Camp Huntsville and other Texas prisoner of war camps in general and the prisoner reeducation programs they utilized lasted long after World War II. During the war Texas, businessmen and farmers who benefitted from the cheap labor provided by POWs tended to support the camps and their reeducation programs. But many other voices—Texans who did not benefit from POW labor, Union leaders, and blue collar Texans who saw the prisoners as competitors for jobs—criticized federal prisoner of war policy in Texas. Such attacks became particularly loud following the invasion of Western Europe as Allied casualties mounted and evidence of the Holocaust came to light. In spring 1945 the offices of Texas Congressmen, the War Department, and the Provost Marshall General were flooded by angry letters from Texans claiming that POW camp commanders were “coddling” prisoners with good food, spacious accommodations, ample opportunities for leisure, and opportunities to earn extra money. Texas newspapers such as the Fort Worth Star Telegram and the San Antonio Express wrote exposés criticizing camp officials for inefficiency and favorable treatment towards their prisoners. After the war, the Provost Marshall’s Office admitted that attempts to keep the Intellectual Diversion Program secret and allowing only limited media access to the camps had ironically sparked public interest in the matter and led to a negative public reaction against such programs. However, the war ended before any sustained criticism could prompt the federal government to change its prisoner of war policies. [44]

One of the greatest ironies of the Intellectual Diversion Program at Camp Huntsville was that it represented an attempt to teach America's sworn enemies the finer points of American democracy in a city and state where African Americans were still treated as second class citizens. During World War II Walker County lay within Texas's seventh congressional district. Out of a population of 299,721 only 11,139 residents in District Seven (or 3.7 percent of the population) voted during 1942. In similar fashion, Out of a statewide population of 6,414,824 Texans in 1940, only 274,627 (4.28 percent of the population) voted in Congressional elections. The widespread use of poll taxes and the disenfranchisement of black voters presumably did not escape the notice of either German and Japanese POWs or the instructors attempting to teach them that the strength of America lay not in its armies but its democratic traditions. [45] One of the greatest ironies of the Intellectual Diversion Program at Camp Huntsville was that it represented an attempt to teach America's sworn enemies the finer points of American democracy in a city and state where African Americans were still treated as second class citizens. During World War II Walker County lay within Texas's seventh congressional district. Out of a population of 299,721 only 11,139 residents in District Seven (or 3.7 percent of the population) voted during 1942. In similar fashion, Out of a statewide population of 6,414,824 Texans in 1940, only 274,627 (4.28 percent of the population) voted in Congressional elections. The widespread use of poll taxes and the disenfranchisement of black voters presumably did not escape the notice of either German and Japanese POWs or the instructors attempting to teach them that the strength of America lay not in its armies but its democratic traditions. [45]

Over the next half century. Scholars have remained divided over the legacy of Camp Huntsville and its prisoner reeducation programs. Judith Gansberg’s Stalag: USA (1977) calls the Special Project Divisons’s Intellectual Diversion Program “one of the most remarkable and successful training programs ever implemented under the auspices of the military.” Ron Robin’s The Barbed Wire College (1995) criticizes the SPD for its elitist, humanist bias, for assuming that hardened German and Japanese soldiers could be reasoned with, and condemns it for registering “no meaningful change in the worldview of the vast majority of the internees.” [46] Richard P. Walker’s The Lone Star and the Swastika (2001), the definitive book on Texas prisoner of war camps, provides a more balanced approach. Walker acknowledges that, “Although the program as envisioned seems to have worthy short-and long-range goals, its actual application left much to be desired . . . .” [47]

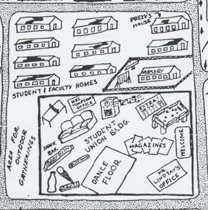

Following the war, Sam Houston State Teachers College (today Sam Houston State University) bought the vacant Camp Huntsville from the federal government. In the 1950s the camp grounds served as temporary dormitory and classroom space. In the 1960s the university’s agriculture department used the nearby land for farming experiments. Today, only the stone gates of Camp Huntsville are left, a silent testimony to a time when German soldiers captured in North Africa and Japanese prisoners of war captured on islands in the Pacific struggled to learn the basics of American democracy and civilization beneath the pine trees of Walker County during the later stages of the Second World War. [48] Following the war, Sam Houston State Teachers College (today Sam Houston State University) bought the vacant Camp Huntsville from the federal government. In the 1950s the camp grounds served as temporary dormitory and classroom space. In the 1960s the university’s agriculture department used the nearby land for farming experiments. Today, only the stone gates of Camp Huntsville are left, a silent testimony to a time when German soldiers captured in North Africa and Japanese prisoners of war captured on islands in the Pacific struggled to learn the basics of American democracy and civilization beneath the pine trees of Walker County during the later stages of the Second World War. [48] |

Endnotes

The Four Freedoms: Teaching Democracy at the Huntsville POW Camp |

|

|

1 Bureau of the Census. 2000 Census of Population and Housing: Estimated Daytime Population: Table Three: Selected Places By State. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census, 2002. [link] (accessed January 15, 2010). See also Ruth Massingill and Ardyth Broadrick Sohn, Prison City: Life With the Death Penalty in Huntsville, Texas (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2007).

2 Bureau of the Census. 1940 Census of Population and Housing: Texas, 805. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census, 1942. http://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/33973538v4p4_TOC.pdf (accessed January 15, 2010).

3 Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. ","http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/HH/heh3.html (accessed January 21, 2010). Randolph B. Campbell, Gone to Texas: A History of the Lone Star State (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 390-397.

4 Campbell, Gone to Texas, 397-398. 5 Arnold P. Krammer, “German Prisoners of War in the United States,” Military Affairs 40 (April 1976), 68.

6 Ibid., 68-69.

7 Richard P. Walker, The Lone Star and the Swastika: Prisoners of War in Texas (Austin: Eakin Press, 2001), 2-3. Walker’s account remains the definitive work for World War II prisoner of war camps in Texas. This article necessarily draws heavily from Walker’s findings.

8 Ibid., 4-5.

9 Krammer, “German Prisoners of War in the United States,” 66-68.

10 Walker, The Lone Star and the Swastika, 51.

11 Ibid., 6-7.

12 Ibid., 7-8, 71-79.

13 Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. "," http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/GG/qug1.html (accessed January 22, 2010).

14 Walker, The Lone Star and the Swastika, 51, 32-33, 61-63. 15 Ibid.,, 6-7.

16 Ibid., 144-145.

17 Krammer, “German Prisoners of War in the United States,” 70.

18 Judith M. Gansberg, Stalag: U.S.A.: The Remarkable Story of German POWs in America (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1977), 54-55.

19 Gansberg, Stalag: USA, 47-51; Michael R. Waters, Mark Long, and William Dickens, Lone Star Stalag: German Prisoners of War at Camp Hearne (College Station: Texas A&M University Press), 102-108.

20 Gansberg, Stalag: USA, 42-43.

21 Ibid., 108-109.

22 Ibid., 48-49.

23 Walker, The Lone Star and the Swastika, 133-134.

24 Ibid.. 128.

25 Ibid., 104-105.

26 Gansberg, Stalag: USA, 59.

27 Ibid., 59-60.

28 Ron Robin, The Barbed-Wire College: Reeducating German POWs in the United States During World War II. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995), 26-28; Ronald H. Bailey, “Lessons in Democracy: The Secret and Controversial Attempt to Teach German POWs About Freedom While They Were Still in Captivity,” World War II (August/September 2009), 52-53.

29 Gansberg, Stalag: USA, 63.

30 Ibid., 63-64.

31 Bailey, “Lessons in Democracy,” 54-55.

32 Walker, The Lone Star and the Swastika, 141.

33 Gansberg, Stalag: USA 60.

34 Walker, The Lone Star and the Swastika, 149.

35 Ibid., 144-145.

36 Bailey, “Lessons in Democracy,” 57; Krammer, “German Prisoners of War in the United States,” 71-72.

37 Bailey, “Lessons in Democracy,” 56-57.

38 Krammer, “Japanese Prisoners of War in America,” Pacific Historical Review 52 (February 1983).

39 Ibid., 88-89.

40 Walker, The Lone Star and the Swastika, 156-157.

41 Ibid., 157.

42 Krammer, “Japanese Prisoners of War in America,” 88-89.

43 Walker, The Lone Star and the Swastika, 159.

44 Ibid., 164-165.

45 78th Congress, 2nd Session, Official Congressional Directory (Washington: GPO, 1944), 256-259.

46 Gansberg, Stalag: USA, 6 and Robin, Barbed-Wire College, 110-111, as cited in William M. Tuttle, Jr., “’Professors into Propagandists’: German POWs and the Failure of Reeducation,” Reviews in American History 25 (March 1997), 121-126.

47 Walker, The Lone Star and the Swastika, 189.

48 Ibid., 187-190. |

|

|

|

|