| |

|

| |

click an image for more information |

Introduction

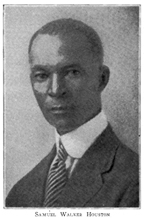

Samuel Walker Houston in Historical Context |

|

|

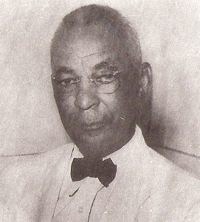

Born around 1871, Samuel Walker Houston was the son of Joshua and Sylvester Houston, two former slaves who lived and worked in Huntsville, Texas. During the 1880s and 90s, Samuel Walker Houston attended the nation's leading black schools, including Atlanta University in Georgia and Howard University in Washington, D.C. At the turn of the century, he returned to Huntsville and founded a training school in the little community of Galilee. Houston's school was one of the first county training schools for African Americans in Texas. It enrolled students at every level, from first grade through high school, and provided a curriculum based on vocational education. Houston's school offered courses in woodworking, construction, and agriculture. To fund his activities, Houston solicited and received support from the Rosenwald Fund, the Slater Fund, and other organizations that assisted the educational pursuits of African Americans. By the time Houston's school merged with the Huntsville Independent School District in 1930, it boasted a dozen teachers and more than 400 students. Based on his remarkable record of achievement, Houston was selected as principal for the new African American high school in Huntsville, which was later named in his honor. |

Background

Margaret Lea, General Sam Houston, and African American Slavery |

|

|

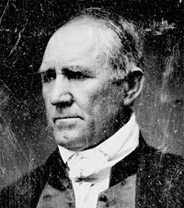

Samuel Walker Houston's story begins more than four decades before his birth in May 1839. That month, two parties converged on Mobile, Alabama, setting the stage for Houston's life and work later in the century. The first party--Nancy Moffette Lea and her twenty-year-old daughter Margaret--came from Marion, Alabama. Mrs. Lea was a wealthy white widow who was traveling to Mobile to speak with her son-in-law, businessman William Bledsoe, about real estate opportunities in the West. Mrs. Lea's daughter, Margaret, had come along on the trip to pay a visit to her sister, the new Antoinette Lea Bledsoe, who was planning a garden party for her friends that spring. Unbeknownst to the Leas, General Sam Houston was headed through Mobile that May as well. In fact, the whole town was soon talking about the Texas hero. A well-known military and political figure, Sam Houston was the commanding general of Texan forces at the Battle of San Jacinto, which had secured Texas' independence from Mexico in 1836. Following independence, Houston had served as the first President of the Republic of Texas until 1838, when he planned a trip through the South to visit his friend, the former President of the United States, Andrew Jackson.

As Houston made his way through Mobile, he was also busily promoting a real estate company that offered properties at Sabine Pass on the Texas gulf coast. It was this endeavor that brought him to the Bledsoe garden party, where he first crossed paths with young Margaret Lea. Despite the dramatic difference in their ages--Houston was 26 years older than Margaret--the two fell in love. In June, Houston asked for her hand in marriage, and one year later the official ceremony was held in Marion at the home of Margaret's older brother, Henry Lea, a businessman and Alabama legislator.

When Sam Houston married Margaret Lea on May 9, 1840, she brought a number of African American slaves to the union. One of these slaves was named Joshua, and he would serve General Sam Houston as a trusted footman, stage driver, and personal assistant. Indeed, more than thirty years later, Joshua Houston named his son, Samuel Walker Houston,

for his long-time master and friend.[1] |

From Slavery to Freedom

Joshua Houston and the Mid-nineteenth Century in Walker County |

|

|

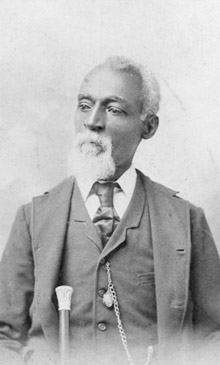

Born in 1822, Joshua Houston was raised as a slave on the Lea plantation near Marion, Alabama. When his master, Temple Lea, died in 1834, ownership of Joshua was transferred to Temple's daughter, Margaret Lea. There seems to have been little change in Joshua's situation, however, until Margaret married Sam Houston in 1840. At that time, Joshua became the property of the most well-known man in Texas, and he soon helped Margaret move to her newly adopted state.

During the 1840s, Joshua learned to read and write, and he became a skilled craftsman. In fact, he used his talents as a blacksmith to help build the Houston home at Raven Hill, thirteen miles east of Huntsville, Texas. Joshua also served the Houston family in a number of other capacities. He repeatedly helped the Houston's move, transferring furniture, books, and other property from Cedar Point and Huntsville to Washington-on-the Brazos, Austin, Independence, and for a time even to Washington D.C. These moves required diligent preparation and a skillful hand as a blacksmith and wheelwright. [2]

Beginning some time around 1850, Sam Houston allowed Joshua to hire out as a stage driver and blacksmith to make money of his own. There was only a small profit to be made in such a situation, however, and it was not until 1862 that Joshua's lot changed for good. That fall, after reading about Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, Sam Houston freed Joshua and his other slaves, encouraging them to go out into the wider world. Most of the slaves stayed with Sam Houston until his death in July 1863, however, and a few of them even traveled with Margaret when she moved to Independence later that year. [3] Beginning some time around 1850, Sam Houston allowed Joshua to hire out as a stage driver and blacksmith to make money of his own. There was only a small profit to be made in such a situation, however, and it was not until 1862 that Joshua's lot changed for good. That fall, after reading about Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, Sam Houston freed Joshua and his other slaves, encouraging them to go out into the wider world. Most of the slaves stayed with Sam Houston until his death in July 1863, however, and a few of them even traveled with Margaret when she moved to Independence later that year. [3]

After the Civil War, Joshua entered an exciting new stage of his life, becoming one of Walker County's leading African American figures. In January 1866, he purchased a tract of land on 10th Street in Huntsville for $120 from Micajah Clark Rogers, the first mayor of the city. In a short time, Joshua had his own two-story house with a blacksmith shop across the street. In fact, his neighborhood grew quickly, and it became known as Rogersville for the beneficent white ally the city's African Americans had in Micajah Rogers. [4]

As Joshua's business developed he played a key role in the local African American church. In April 1867, he joined with William Baines and Strother Green as "trustees for the Freed people's church in the Town of Huntsville." For $50, Joshua and his friends bought property three blocks from the local square, and they became founding member of the new Union Church, which was the first black-owned church in the city. The Union Church served both Baptists and Methodists, and it was also the site of one of the earliest black schools in Huntsville. As Patricia Prather and Jane Monday have argued, "This became the first institution in Huntsville owned collectively by ex-slaves and thus subject to their control. It became much more than a religious institution. Freedmen often met there to share information about how to protect themselves and their families. The church also became an education center where both children and adults began learning to read the Bible and the few other books that were available to them." [5]

Although Joshua no doubt loved the Union Church, the congregation soon grew too large and diverse for a single location. The church split into three separate groups in January 1869. The Methodist Episcopal congregation founded St. James Methodist Episcopal Church at the “Union” site at 14th Street and Avenue M. Members of the African Methodist Episcopal faith founded Allen Chapel AME church on Avenue I and 11th Street a few years later. Meanwhile, Joshua and several dozen other Baptists established the First Baptist Church on 10th Street in Rogersville. It was there that Joshua emerged as a deacon and one of the city's leading figures during Reconstruction. [6]

Although he was busy with church and business obligations, Joshua's public duties took on an additional dimension in 1867, when he was appointed as Huntsville's first African American alderman. As a well-known black Republican and the former slave of a Union sympathizer, Joshua was the type of man Republicans in Texas wanted for their ranks. He was literate; he owned his own business; and he was recognized as a leader in his local community. As the Republican Party enacted a new Military Reconstruction program to stamp out discriminatory state laws and secure a new state constitution, Joshua joined forces with the party at the local level. He was reappointed to the alderman's position in 1870 and was later elected, under the new Texas Constitution, as a county commissioner in 1878 and 1882. Perhaps his greatest political endeavor came in 1888, when he served as a member of the Texas delegation to the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Illinois. [7]

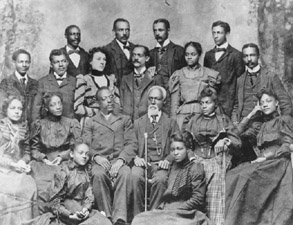

Despite his important work in the political arena, it was in education that Joshua made his most lasting impact. He had been a founding trustee of the first African American school in Huntsville at the Union Church. He was a friend and supporter of the six freedmen--Richard Williams, Joseph Morris, Allen Justice, Green Justice, Sam Sims, and Anderson Bates--who founded a school at Grant's colony, a few miles west of Huntsville. And, Joshua Houston was among a group of thirty or so activists--including Memphis Allen, Alex Wynne, Will Mills, Strother Green, John Wilson, and William Kittrell--who founded and promoted Bishop Ward College in 1883. Although the school failed two years later, due to a lack of funds, Joshua's children and others their age received an enormous jolt from the short-lived project. In fact, it may have been at Bishop Ward that Joshua's son, Samuel Walker Houston, met Professor C.W. Luckie, who encouraged the young boy to pursue his education outside the state of Texas.[8]

By the time Joshua died on January 8, 1902, he had been married three times -- to Anneliza, Mary Green, and Sylvester Baker -- and he had eight children. It is to his son, Samuel Walker Houston, that we must now turn our attention. |

A Childhood in Freedom

Samuel Walker Houston Grows Up in Huntsville |

|

|

Black Schools in the

Huntsville Area

During Reconstruction |

1 - Freedmen's Bureau School

“The first Negro school built in Old Huntsville was ... after the war. It was situated west of the branch behind “Item Robinson’s” home, near Mrs. Plummer’s home, and was taught by a Northern woman .... The Negroes were keen to learn to read and write, and her school was always full to overflowing.” [11] |

2 - Union / St. James Methodist School

Local teacher David Williams pointed out that St. James church was used as one of the city’s school for African American children. The teachers included five “white teachers from the North,” -- Lizzie Stone, Texana Snow, and three individuals named Ausbourn, James, and Brown. These people were succeeded by black teachers, including Jacob F. Cozier, O. A. Todd, and Mollie Flood. [12] |

3 - Trinity River School

Freedmen's Bureau agent, James P. Butler, in his Monthly Report on June 30 1867, highlighted a school with 20 students on the Trinity River taught by John Rogers.[13] |

4 - Stubblefield's Mill School

Freedmen's Bureau agent, James P. Butler, in his Monthly Report on June 30 1867, highlighted another school with 15 students at Stubblefield’s Mill taught by Sarah Whitman. [14] |

5 - Grant’s Colony school

On September 9, 1868, six trustees from Grant’s colony, a freedmen's settlement five miles west of Huntsville, requested land for a new school, which was ultimately called the Harmony Grove School.

The school was supported by the Freedmen's Bureau and it was under the direction of a Quaker from Ohio, Dr. E.H. Williams.[15] |

|

It appears that Samuel Walker Houston was born in Huntsville, Texas, sometime between 1864 and 1871. This means that Houston came into the world shortly after his parents had won their freedom. In fact, this may very well explain why Joshua and Sylvester named their son after their former owner, General Sam Houston. [9]

Whatever the case, it is clear that Samuel Walker Houston grew up in a world quite different from the one his parents had experienced in the 1820s and 30s. To begin with, in June 1865, following the conclusion of the Civil War, word came to Texas that all enslaved people living in the state were now free. While this news did not immediately usher in a new order of racial equality, it did mean that African Americans living in Texas would have many opportunities their ancestors had never enjoyed.

The first and most obvious advantage Samuel Walker Houston enjoyed was the opportunity to attend school. While there is little direct primary evidence available, it seems clear that Houston enrolled in one of the local schools that cropped up in Huntsville during Reconstruction. We know from oral testimony that Houston learned how to read and write at an early age. This meant that Houston was likely one of the many students who benefited from the educational work of the Freedmen's Bureau, which reported in September 1868 that there were at least 47 schools, 45 teachers and more than 1550 African American students in all of Texas.[10]

By the time Joshua Houston and other local leaders established Bishop Ward College in 1883, Samuel was somewhere between the ages of twelve and nineteen. Although the Bishop Ward school closed in 1885, evidence suggests that Houston met and worked with one of the school's best teachers, Professor C. W. Luckie. An 1883 graduate of Atlanta University, Luckie was an accomplished teacher, and he encouraged Samuel Walker Houston to further his education by traveling outside Texas.

|

Outside the Lone Star State

Samuel Walker Houston Attends School and Works Outside the State |

|

|

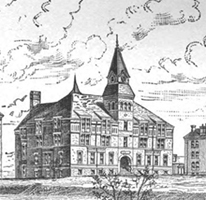

Samuel Walker Houston left Huntsville sometime in the mid-1880s to pursue higher education outside of Texas. Although we know very little about the exact route he took or the plans he had, we can piece together the main outline of his education by looking at university catalogs of the period. These sources include not only the names of students, but also list particular courses of study and extracurricular activities. From the catalogs, it seems clear that Houston began his higher education as a high school senior in the College Preparatory program at Atlanta University in 1887-88. Then, a year later he enrolled as a undergraduate student at the school. Samuel Walker Houston left Huntsville sometime in the mid-1880s to pursue higher education outside of Texas. Although we know very little about the exact route he took or the plans he had, we can piece together the main outline of his education by looking at university catalogs of the period. These sources include not only the names of students, but also list particular courses of study and extracurricular activities. From the catalogs, it seems clear that Houston began his higher education as a high school senior in the College Preparatory program at Atlanta University in 1887-88. Then, a year later he enrolled as a undergraduate student at the school.

While at Atlanta University, Houston was apparently called the "other Sam Houston," an appellation that identified him with his father's ex-master. He was a popular student and played on the baseball team with James Weldon Johnson, who later became one of America's most well-known black authors. Johnson and his brother composed the song ''Lift Every Voice and Sing," which became known as the Negro National Anthem.

It appears that Houston left Atlanta University some time around 1890 and went to Washington D.C., where he enrolled at Howard University. In the 1927 Who's Who in Colored America, Houston noted that he attended Howard between 1891 and 1894, although it has been impossible to verify this information. Houston is not listed in the catalog of students, nor does Howard University hold a transcript for him. This means that Houston's course of study and graduation date remain illusive.

After he attended school at Howard, it seems that Houston took a job working as a government clerk in the Old Ford Theater building, where President Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated. During his five-year stint in then nation's capital, Houston worked for the War, State and Navy Departments. [16]

|

Houston Returns to Texas

Samuel Walker Houston Attends School and Works Outside the State |

|

|

When Samuel Walker Houston returned to Huntsville around 1900, he quickly established a newspaper--the Huntsville Times--for the city's black citizens. Like the white-owned papers of the period, Houston's publication informed its readers about local, state, and national events of interest to local residents. We can assume that the paper also covered specific information of interest to blacks, which most white newspapers refused to publish.

While working on his paper, Houston also made great strides in his personal life. On June 4, 1901, he married a long-time family friend, Cornelia Orviss. Cornelia was the daughter of Reverend George and Mary Orviss, who served as the ministers at First Baptist Church in Huntsville. Cornelia and Samuel had known one another for years, and her sister, Georgia Carolina, was married to Samuel's brother, Joshua Houston, Jr. About a year after the marriage the young newlyweds had a son named Harold. And, very soon thereafter, Cornelia became pregnant again. Sadly, however, Cornelia and her baby girl died in childbirth. While working on his paper, Houston also made great strides in his personal life. On June 4, 1901, he married a long-time family friend, Cornelia Orviss. Cornelia was the daughter of Reverend George and Mary Orviss, who served as the ministers at First Baptist Church in Huntsville. Cornelia and Samuel had known one another for years, and her sister, Georgia Carolina, was married to Samuel's brother, Joshua Houston, Jr. About a year after the marriage the young newlyweds had a son named Harold. And, very soon thereafter, Cornelia became pregnant again. Sadly, however, Cornelia and her baby girl died in childbirth.

Although we can never known the pain that Houston felt at the death of his wife and daughter, it seems clear that he was devastated by their loss. He soon sent his son Harold to live with his in-laws and moved to the Red HIll community in Grimes County to teach at the local community school. A short time later, however, Houston decided to return to the Huntsville area to be near family and friends. [17]

|

An African American Training School

Samuel Walker Houston, the Galilee Community, and the Houston School |

|

|

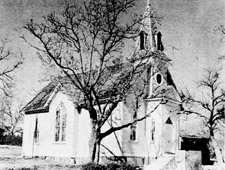

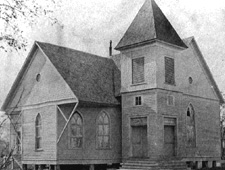

In 1906, Samuel Walker Houston moved to the small community of Galilee, located about five miles west of Huntsville. There, he accepted a teaching post in a tiny African American school that met in a twelve-by-fourteen foot hut that had previously served as a private home. The school was in such poor repair that Houston refused to use the building. Instead, he paid $4 of his own $35 monthly salary to rent the Galilee Methodist Church. There, he and his assistant, Mamie Arnold, taught students in grades one through six. In 1906, Samuel Walker Houston moved to the small community of Galilee, located about five miles west of Huntsville. There, he accepted a teaching post in a tiny African American school that met in a twelve-by-fourteen foot hut that had previously served as a private home. The school was in such poor repair that Houston refused to use the building. Instead, he paid $4 of his own $35 monthly salary to rent the Galilee Methodist Church. There, he and his assistant, Mamie Arnold, taught students in grades one through six.

During the year, Houston expanded his efforts at the Galilee school. First, he formed a Board of Trustees, including John Randall, Milton Jones, Eastern Dickie, Bud Mills, Noble Naylor, Sterling Jones, Adam Walker, Bill Williams, Nathan O'Neals, Henderson Naylor, and W. H. Appling. Next, he secured the donation of one acre of land from Melinda Williams for the construction of a new school building, which would become known as the Sam Houston Industrial and Training School. (See the Warranty deed—filed 1 December 1906).

Once the initial outlay of land had been secured, the trustees and students began a series of programs to raise money for construction at the new site. They hosted concerts, bake sales, baseball games, and other events that eventually paid for a four-room school, with a vocational shop, and basic supplies. As the student population rose, new teachers were added as well. J. Paul Chretien was hired to teach manual training, Jack Beauchamp taught woodwork and Hope G. Harville, a graduate of Tuskegee, was hired to teach homemaking. Eventually, an additional 4.5 acres was purchased to add dormitories and other facilities.

The curriculum at Houston's school was based primarily on the educational philosophy espoused by Samuel Chapman Armstrong, the founder and first principal at Hampton Institute. Born to white missionaries in Hawaii, Armstrong graduated from Williams College in Massachusetts before volunteering to serve in the Union Army during the American Civil War. During the war, Armstrong commanded the 8th U.S. Colored Troops and established a school to educate black soldiers, most of whom had been denied an education as slaves. After the Civil War, Armstrong joined the Freedmen's Bureau and helped establish Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Hampton, Virginia (1868). He intended the school to include manual and industrial education, which would promote hard work, self-discipline, and self-reliance. His manual labor program enabled many impoverished African Americans to support themselves during their three years of teacher training at Hampton. Armstrong's most famous students was Booker T. Washington, who followed the Hampton model when he started Tuskegee Institute in 1881. The curriculum at Houston's school was based primarily on the educational philosophy espoused by Samuel Chapman Armstrong, the founder and first principal at Hampton Institute. Born to white missionaries in Hawaii, Armstrong graduated from Williams College in Massachusetts before volunteering to serve in the Union Army during the American Civil War. During the war, Armstrong commanded the 8th U.S. Colored Troops and established a school to educate black soldiers, most of whom had been denied an education as slaves. After the Civil War, Armstrong joined the Freedmen's Bureau and helped establish Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Hampton, Virginia (1868). He intended the school to include manual and industrial education, which would promote hard work, self-discipline, and self-reliance. His manual labor program enabled many impoverished African Americans to support themselves during their three years of teacher training at Hampton. Armstrong's most famous students was Booker T. Washington, who followed the Hampton model when he started Tuskegee Institute in 1881.

For all of Armstrong’s good intentions, however, he “combined arrogance with paternalism in his dealings with those whom he set out to serve.” In fact, his educational philosophy--which became known as the Hampton-Tuskegee method--grew increasingly controversial. By the 1890s, critics of vocational education, including the great African American sociologist and historian W.E.B. Du Bois, called for a classical liberal arts education for African Americans.

At the Galilee school, Samuel Walker Houston drew primarily on the vocational form of education. Young women were trained in homemaking, sewing, and cooking, while young men learned carpentry, woodworking, and basic mathematics. In addition, there were classes in music, educational philosophy, and the humanities as well.

While teaching in Galilee, Houston fell in love with Hope Harville, a fellow teacher at the school. The two were married on April 28, 1915, and they moved into a house across the street from the school. The couple soon had several children and led the community by their example.

As Houston's school grew, he applied for and received $300 from the Quaker Fund in Philadelphia. He also received financial support from the Rosenwald Fund, the Slater Fund, W. S. Gibbs, and H.C. Meachum. When Houston finally received support from the Texas General Education Fund, he and the other trustees turned over their assets to Walker County, and the Sam Houston Institute became part of the Texas education system.

By 1922, enrollment at Houston's school had grown to 400 students. It was described by P. R. Thomas as "the leading school of East Texas, [which] had advanced under the leadership of the sage, Professor Houston . . . from a low[ly] hut to a low estimate of $15,000," the school was rated as the best rural black school in Texas. In 1930, at Houston's request, his school was incorporated into the Huntsville Independent School District. He then became the County Superintendent of Schools and then principal of the new high school that was later named in his honor.

Mr. Houston delivered his last public speech at the commencement of the 1944 graduating class of Sam Houston High School in Huntsville. He told the graduates: "True humility is a necessary quality for one who would be successful in the accomplishment of a great task. Another quality that is required for one who would be a leader is courage. He is not a real leader unless his courage remains steadfast and he can move forward with his convictions whether there is a visible majority with him or not." Samuel Walker Houston died on November 19, 1945, and was buried in Huntsville's Oakwood Cemetery. [18]

|

Footnotes

Samuel Walker Houston and the African American Training School at Galilee |

|

|

[1] The story of Margaret Lea and Sam Houston's meeting may be found in

William Seale, Sam Houston's Wife: A Biography of Margaret Lea Houston (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970), 10-11. For another version, see:

Madge Thornall Roberts, Star of Destiny: The Private Life of Sam and Margaret Houston (Denton: University of North Texas Press, 1993) 17-30. [1] The story of Margaret Lea and Sam Houston's meeting may be found in

William Seale, Sam Houston's Wife: A Biography of Margaret Lea Houston (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970), 10-11. For another version, see:

Madge Thornall Roberts, Star of Destiny: The Private Life of Sam and Margaret Houston (Denton: University of North Texas Press, 1993) 17-30.

[2] Patricia Smith Prather and Jane Clements Monday, From Slave to Statesman: The Legacy of Joshua Houston, Servant to Sam Houston (Denton: University of North Texas Press, 1993), 10-70.

[3] Ibid., 71-75.

[4] Ibid., 87.

[5] Ibid., 97.

[6] Ibid., 119-126.

[7] Ibid., 117-187.

[8] Ibid., 109-110, 170-171.

[9] The date of Samuel Walker Houston's birth is unclear. His tombstone in Huntsville's Oakwood Cemetery provides a date of 1864, which Naomi Lede, Patricia Smith Prather, and Jane Clements Monday all support. I do not believe this date is accurate for a number of reasons. 1) Samuel Walker Houston was not listed with his family in the 1870 census. 2) When he was listed with the family in the 1880 census, Houston's family claimed that he was 11 years old. 3) Furthermore, Samuel Walker Houston listed his own date of birth as 1871 in Who's Who in Colored America for 1927. 4) Then, in 1940, Houston signed an affidavit stating that he was born in 1874.

I believe that 1870-71 is the most likely date for Houston's birth. This would explain why he is not listed in the 1870 census; why he appears as 11 years-old in the 1880 census; and why he himself would claim that birth date at the height of his educational and social life. Furthermore, it seems to be supported by other facts. For instance, Houston enrolled as a pre-collegiate student at Atlanta University in 1887, and then entered as a freshman in 1888. This would make him seventeen or eighteen when he entered college as a freshman, which seems like the appropriate age given his family's background and educational connections (i.e. C.W. Luckie).

For copies of all the sources mentioned above, click here to download a pdf file.

[10] Prather and Monday, From Slave to Statesman, 110.

[11] Charles Taylor Rather, “Around the Square in 1862 with a Barefoot Boy,” in D’Anne McAdams Crews, ed., Huntsville and Walker County, Texas: A Bicentennial History (Huntsville: Sam Houston State University Press, 1976), 142. Available online click here.

This story was confirmed in other sources as well.

In his October 20, 1866 report, Captain James Devine, the branch agent of the Freedmen’s Bureau in Huntsville, reported to his superiors that there was “a white lady teaching school” in town. (James Devine to J.B. Kidds, October 20, 1866, Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Estelle Owens Collection, Texas State Archives, Austin Texas, Microfilm Reel 3386). Further confirmation may be found in a subsequent report submitted by Huntsville’s second Freedmen’s Bureau Agent, James P. Butler, who wrote in his Monthly Report on June 30 1867 that a school with twenty students was being taught by Mrs. or Miss Tanner. (James P. Butler, Monthly Report, June 30, 1867, Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Microfilm Reel 3385). Freedmen’s Bureau Schools would be discontinued on June 30, 1870, when the Bureau itself was ceased its operations. The Freedmen’s Bureau school in Huntsville was well established, however, and continued after 1870 with monies raised in the local community. See Prather and Monday for more information.

[12] Rev. C. W. Wilson report, “The Negro in Walker County,” (1934). The Union church as a formal entity and location was short-lived. It lasted from April 1867 (when the land was actually purchased) to January 1869 (after the church divided and when the formal title to the church and land was transferred). See Scott E. Johnson, “The History of Early Negro Churches in Huntsville, Emancipation Park, and Local Negroes in Reconstruction Politics,” in D’Anne McAdams Crews, ed., Huntsville and Walker County, Texas: A Bicentennial History (Huntsville: Sam Houston State University Press, 1976), 82-84. Available online click here.

[13] James P. Butler, Monthly Report, June 30, 1867, Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Microfilm Reel 3385.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Prather and Monday, From Slave to Statesman, 179.

[16] The information presented here come from several sources. The traditional biography of Samuel Walker Houston is presented in Naomi Lede's work, Samuel W. Houston and His Contemporaries:

A Comprehensive History of the Origin, Growth, and Development of the Black Educational Movement in Huntsville and Walker County(Printed by Pha Green Printing, Inc., 1981). For Houston's enrollment at Atlanta University, see the Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Atlanta University, Atlanta, Georgia, with a Statement of the Courses of Study, Expenses, Etc. 1887-88 and 1888-89 (available as pdf here). For Houston's entry in the 1927 Who's Who in Colored America click here for a pdf file.

[17] Lede, Samuel W. Houston and His Contemporaries, 21-26; Prather and Monday, From Slave to Statesman, 200-203.

[18] Material in this section drawn from Lede, Samuel W. Houston and His Contemporaries, 26-48; Prather and Monday, From Slave to Statesman, 203-221.

OTHER SOURCES OF INTEREST

Paul Sugg, “The Freedmen’s Bureau in Walker County,” Masters thesis, Sam Houston State University, 1990.

James Devine reports. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Estelle Owens Collection, Texas State Archives, Austin Texas, Microfilm Reel 3386, 3393.

Walker County Genealogical Society and Walker County Historical Commission, Walker County, Texas: A History (Dallas: Curtis Media Corporation, 1986).

P.R. Thomas, Outline History of the First Baptist Church, Huntsville, Texas (Huntsville, published privately, 1923).

C.W. Wilson, “The Negro in Walker County,” (Huntsville: Sam Houston State University, 1934).

|

|

|

|

|